Western Blotting

Western blotting is a popular molecular biology technique used to detect the presence of specific proteins within a heterogeneous sample. For example, western blot can help scientists:

- Verify expression of a protein of interest in an overexpression strain

- Detect up- or down-regulated protein expression

- Detect post-translational modification

- Diagnose disease by detecting protein biomarkers

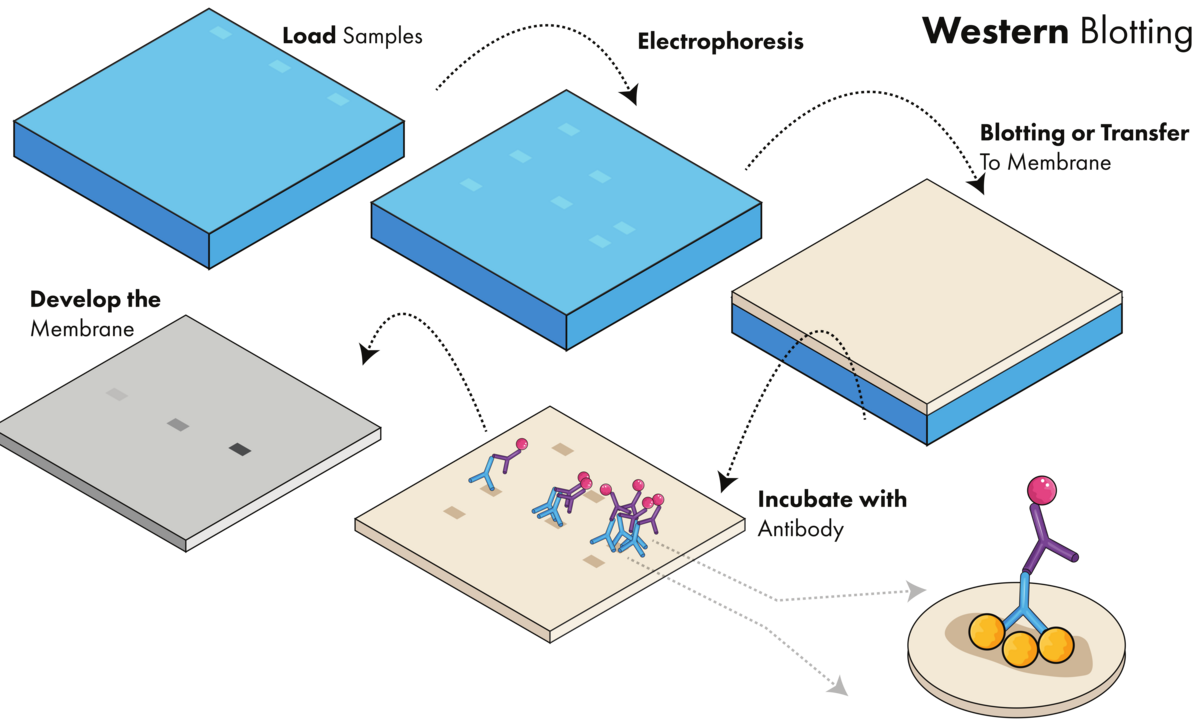

A western blot experiment can be broken down into three steps (Figure 1):

- Separating a mixture of proteins based on their size using gel electrophoresis

- Transferring all proteins from the gel to a membrane

- Detecting the protein of interest using a combination of antibodies and visualization techniques

Western blotting requires loading the sample onto a gel, running the gel, transferring the proteins to a membrane, incubating with antibody, and developing the membrane to visualize proteins of interest.

Protein Separation

Extracting proteins from samples and separating the proteins is the first stage of the western blot method. The exact steps can vary based on the sample type and the complexity of the protein mixture.

Protein Extraction

Methods required to extract proteins from samples will range in complexity. Common methods include both physical and chemical processes, including sonication, enzymatic digestion, freeze/thaws, or exposure to detergents. The overall idea is to release the proteins from the cells.

Before loading samples onto the gel, it’s important to measure the total protein concentration of each sample. This can be done using assays like the bicinchoninic acid assay or the Bradford assay. Then, samples can be normalized so that you load the same amount of protein into each well. For denaturing gels, a loading dye containing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is added to the sample to give the protein a net negative charge and will fully expose potential binding epitopes for antibody interaction.

Gel Electrophoresis

Protein separation is performed by loading prepared samples into a polyacrylamide gel and applying an electric field. Beside your samples, you will use one lane of the gel to run a molecular weight ladder. The ladder contains dyed proteins of known molecular weights which are used as a comparison point to estimate the size of proteins of interest in the sample.

Denaturing western blots use sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), which removes the secondary and tertiary structures of the protein. That way, proteins can be separated by size as they run through the gel. Smaller proteins migrate faster through the matrix while larger proteins migrate slower. This separation forms distinct bands on the gel for further analysis.

Varying the gel percentage can help separate difficult to resolve proteins. Small proteins are better resolved using gels with higher percentages of acrylamide while larger proteins are better resolved in gels with lower percentages of acrylamide. There are also gels that contain a gradient of acrylamide concentrations (ex: 4-20%) where the concentration of acrylamide increases towards the bottom of the gel. This is useful if you need to resolve a wide range of protein sizes in the same gel.

Native PAGE: An alternative to denaturing gels is native PAGE. Native PAGE gels do not contain SDS and preserve the protein’s structure. Instead of separating proteins by size, they are separated by charge and size, where the protein’s tertiary structure impacts migration. Proteins that fold more compactly will migrate faster compared to proteins with the same molecular weight that have a larger 3-D structure.

For the remainder of this article, we will refer only to the widely-used SDS-PAGE.

Protein Transfer

After separating a mixture of proteins, the resulting protein bands must be transferred to a membrane before the protein of interest can be probed and visualized.

Transfer Proteins to a Membrane

Once separated, the proteins are then transferred from the gel to a membrane (ex: PVDF or nitrocellulose). This is done by laying the membrane against the gel, and applying an electrical current in a buffer so that proteins move from the gel to the membrane. This transfer can happen either as a wet transfer, where the membrane and the gel are completely submerged in the buffer, a semi-dry transfer where only the transfer cassette is submerged, or a dry transfer, which requires specialized equipment. After transfer, you can verify that all proteins in the gel have transferred to the membrane using Ponceau staining, which stains all proteins.

Blocking Non-specific Sites

Once transferred, a blocking reagent is required to prevent unwanted protein from binding to the membrane. Because the membrane contains sites that aren’t bound by protein, any additional proteins used in subsequent steps (ex: antibodies) will nonspecifically bind the membrane. Blocking these sites is accomplisheddone by incubating the membrane with a solution of milk or other non-reacting protein, such as BSA.

Protein Detection

Now, your protein of interest is ready for detection. This step uses of primary and secondary antibodies to detect the target proteins.

Primary and Secondary Antibodies

Proteins of interest can be detected in one of two ways: direct detection or indirect detection.

In both methods, membranes are treated with a primary antibody that is designed to specifically bind the target protein (Figure 2). In direct western blots, the primary antibody is conjugated to an enzyme or a fluorophore that is used for detection. Indirect detection requires a secondary antibody, which binds to the primary antibody. In indirect detection, the secondary antibody, rather than the primary antibody, is conjugated with the enzyme or fluorophore.

Secondary antibodies are useful to help amplify the signal as multiple secondary antibodies can bind to a single primary antibody. Selecting antibodies for western blot means considering both the detection method as well as the species that the primary antibody was generated in.

When using primary and secondary antibodies, their concentrations often need to be tested against the specific sample. For example, using an antibody that’s too concentrated could result in nonspecific signal or oversaturated blots, while using an antibody dilution that is too dilute could result in low levels of detection. Recommended ranges for antibody dilutions can often be found on the antibody’s product page and is especially helpful if that antibody has been validated for western blot applications. Typically, these concentrations are between 1:500 to 1:10,000 for primary antibodies and between 1:1,000 to 1:30,000 for secondary antibodies.

As mentioned above, membranes can be stripped of antibodies and reprobed if you need to detect additional targets or reoptimize antibody dilutions. Stripping and reprobing membranes isare not compatible with detection methods that leave colorimetric reagents on the membrane. It’s also possible to cut the membrane to incubate different portions with different antibodies if the proteins of interest are of different sizes.

Detection Methods

Once the antibodies have bound any proteins of interest on the blots, they can then be detected using a variety of enzymatic or fluorescence-based methods. These include:

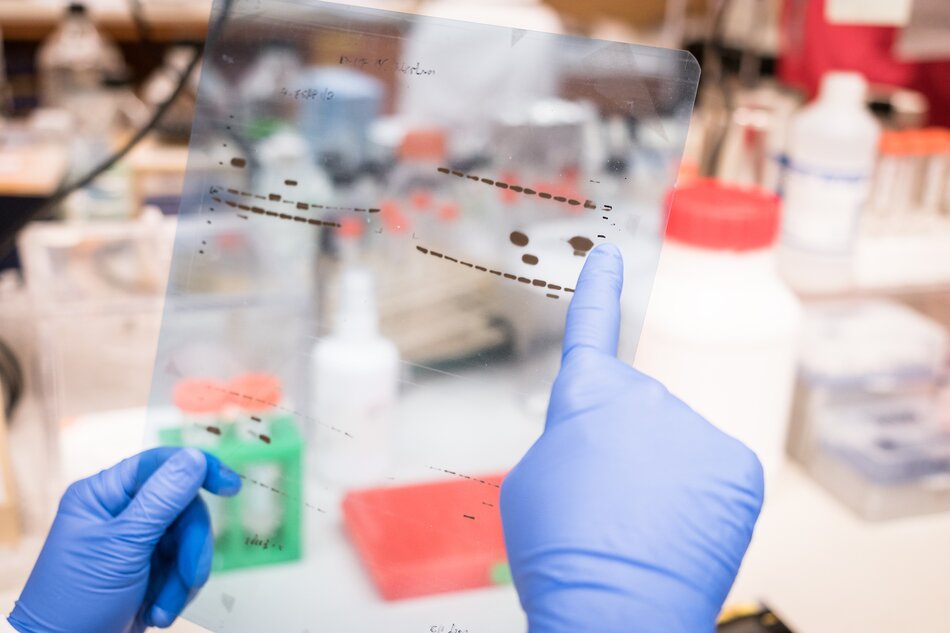

- Chemiluminescence: Antibodies are conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP). HRP generates light when incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents. Light is detected by an imaging system or on X-ray film (Figure 3).

- Fluorescence: Fluorophores conjugated to antibodies are excited with a light source and captured by CCD camera.

- Alkaline phosphatase: Antibodies are conjugated with alkaline phosphatase, which catalyze a color change on the membrane when incubated with BCIP/NBT.

Western blots can be semi-quantitative as protein levels can be compared relative to one another. To do this, a housekeeping protein that has the same expression level across all samples is used as a comparison point for the protein of interest. By comparing the signal of the protein of interest to the control, you can determine relative expression levels between samples.

Western blot results on X-ray film.

Protocols

Our western blot protocols help to guide you through your next experiment.

Western Blot FAQs

What protocol was used to perform the blot shown in the data sheet of Bethyl antibodies?

If I do not use a ReliaBLOT® kit, what blocking buffer should I use?

Can you give me the exact sequence of the immunogen used to generate the antibody I purchased?

Why is my band/signal not migrating at the same size that you show in your data sheet?

Why do some proteins not migrate at the predicted molecular weight?